Disclaimer: This post goes into the following subjects: Abuse, Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD), Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), rape, substance abuse, and suicide. If these topics make you uncomfortable, please do not read this, as your mental health is far more important than you reacting to this blog post. Also, let me stress that I am no expert on mental health. Any and all information that I recite comes from various sources that I will cite at the end.

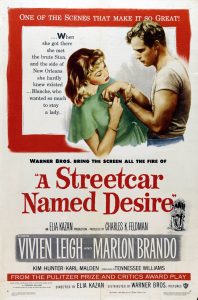

Jesus Christ, where do I begin with this? At the start of A Streetcar Named Desire, Blanche DuBois seemed like your average white Southern Belle during the 20th century. We first see her arriving in New Orleans to visit her sister, Stella Kowalski. After catching up with each other over drinks and cigarettes, Blanche meets her brother-in-law, Stanley Kowalski, after returning home from bowling with the guys. As I said, it was a pretty normal evening, until a small throwaway moment caught my eye. When a cat screeched outside of the house, Blanche jumped. While a noisy cat would be a normal occurrence around the area, noted by Stanley acting nonchalant about it while answering Blanche’s question, Blanche was spooked. Anyone would jump at sudden loud noises when we least expect it. Minutes later, she fainted after Stanley inquired about her late husband. Later on, Blanche retells the story of what happened to her late husband. According to Blanche, her husband took his own life by shooting himself with a gun. Her hesitancy to speak about her late husband to being easily startled by sudden noises points to Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. Other symptoms that she displays are severe emotional responses to events that remind her of the traumatic event (Scene six when she flinches upon hearing a train and scene nine when “Varsouvania” replays in her mind), self-destructive behavior (In scene nine, she was drinking heavily when the polka song replays in her mind before Mitch arrived), and intrusive flashbacks (Scene nine when she “hears” both the song as well as the gunshot). This particular event stayed with her, and it affects her greatly even though it’s likely to have been about a decade or so ago. Due to her not seeking actual help and therapy, her PTSD has worsened over time.

Blanche isn’t just suffering from PTSD. It appears that she also developed Borderline Personality Disorder, a mental health disorder that affects her ability to control her emotions. This also comes with the caveat that any and all relationships that she had were rocky. In scene eight, Stella said that Blanche was taken advantage of and abused when she was very young. We don’t really have a rough timeline of when that occurred, but it likely happened when she was most likely a teen. BPD is likely to occur in children and teens who suffered from traumatic events with very little to no support. In scene nine, she clung onto Mitch like a vice, and when she was suffering from a flashback, she seemed to calm down for a while when Mitch kissed her. This leads me to believe that her means of “escape” from the past was in the arms of a man. This would explain why she slept around during her temporary stay at The Flamingo, as well as her scandal that caused her to be fired from her teaching position and chased out of town (Stanley gives her a bus ticket back to Laurel, which is ironic considering her said that she all but banished from town).

For Blanche, her having PTSD and BPD is no doubt a constant struggle for her. She appears to have taken to hydrotherapy in order to help with her nerves. Sadly, it would only work for a brief period until she has another episode. What really drove her over the edge was in scene ten was when Stanley raped her while taking advantage of her fragile mental state. Let’s not mince words here, Stanley is a piece of shit for doing this to Blanche. He made things worse for her after that. Stella sending her sister off to a mental hospital may have helped her in the end (Though let’s be honest, Stella and her son aren’t safe as long as they’re living with Stanley). In the finale, Blanche didn’t want to leave the bedroom when the Doctor and the Matron arrived because she knew Stanley was there.

And finally, let’s address the polka music. “Varsouvania” would be playing whenever Blanche’s mental fortitude is shattered. For example, the song starts playing in scene six as she was telling Mitch about her late husband’s suicide. Blanche said that song was playing on the night her husband died. Since then, that song is linked to her emotional turmoil, regardless of whether the song was played in a major key or minor key (In the world of music, major keys denote bright, happier feelings, whereas minor keys are more somber, darker moods). If she were in a much more frantic state, like in scene nine, the polka song would be louder and more hectic. At the beginning of a mental breakdown, the song would be playing faintly in the distance.

Work Cited

“Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) – Symptoms and Causes.” Mayo Clinic, 6 July 2018, www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/post-traumatic-stress-disorder/symptoms-causes/syc-20355967.

https://www.borderlinepersonalitydisorder.org/what-is-bpd/bpd-overview/

In the background, propelling the story, is the trauma response that Blanche is enduring. She witnesses her young husband’s suicide after catching him engaged in sexual activities with another man. The way that Blanche talks about him gives the impression that she blames herself. She calls him just a boy and speaks of how she hurt him. Whenever she does talk about him, it is accompanied by the sound of an approaching train, which brings her inner turmoil to the physical world.

In the background, propelling the story, is the trauma response that Blanche is enduring. She witnesses her young husband’s suicide after catching him engaged in sexual activities with another man. The way that Blanche talks about him gives the impression that she blames herself. She calls him just a boy and speaks of how she hurt him. Whenever she does talk about him, it is accompanied by the sound of an approaching train, which brings her inner turmoil to the physical world. he idea that desire leads to the cemetery which represents death and then Elysian Fields which is known as the afterlife. Blanche is led to this afterlife because she had been acting promiscuously back in her hometown of Laurel by seducing not only young men but also her underage students. When Blanche explains her travel on the train car named Desire it sounds awfully like her circumstances when the readers enter the play.

he idea that desire leads to the cemetery which represents death and then Elysian Fields which is known as the afterlife. Blanche is led to this afterlife because she had been acting promiscuously back in her hometown of Laurel by seducing not only young men but also her underage students. When Blanche explains her travel on the train car named Desire it sounds awfully like her circumstances when the readers enter the play.

ing A Streetcar Named Desire, something that stood out to me was the usage and placement within the stage directions for musical cues, as well as the type of music to be used for the scene. I went back through the book several times to count and infer where elements of the score were implemented and counted twenty-two times the ‘blue piano’ music was directly mentioned or inferred (including clarinet, trumpet, and drums accompaniment), and sixteen times that the polka–the ‘Varsouviana’–was directly mentioned. At the beginning of the book, the stage notes say what exactly the ‘blue piano’ music was meant to represent, which was the ‘spirit of life which goes on here.’ As for the polka, that is left for the audience to interpret as they will, but it is most prominently played whenever references to Blanche’s past are talked about or even, presumably, when Blanche even thinks about her past. The first time the polka plays is during scene one, when Stanley (rudely) asks Blanche if it’s true that she was married once. This could be interpreted as foreshadowing as the music is so starkly different from the jazz New Orleans is known for.

ing A Streetcar Named Desire, something that stood out to me was the usage and placement within the stage directions for musical cues, as well as the type of music to be used for the scene. I went back through the book several times to count and infer where elements of the score were implemented and counted twenty-two times the ‘blue piano’ music was directly mentioned or inferred (including clarinet, trumpet, and drums accompaniment), and sixteen times that the polka–the ‘Varsouviana’–was directly mentioned. At the beginning of the book, the stage notes say what exactly the ‘blue piano’ music was meant to represent, which was the ‘spirit of life which goes on here.’ As for the polka, that is left for the audience to interpret as they will, but it is most prominently played whenever references to Blanche’s past are talked about or even, presumably, when Blanche even thinks about her past. The first time the polka plays is during scene one, when Stanley (rudely) asks Blanche if it’s true that she was married once. This could be interpreted as foreshadowing as the music is so starkly different from the jazz New Orleans is known for.