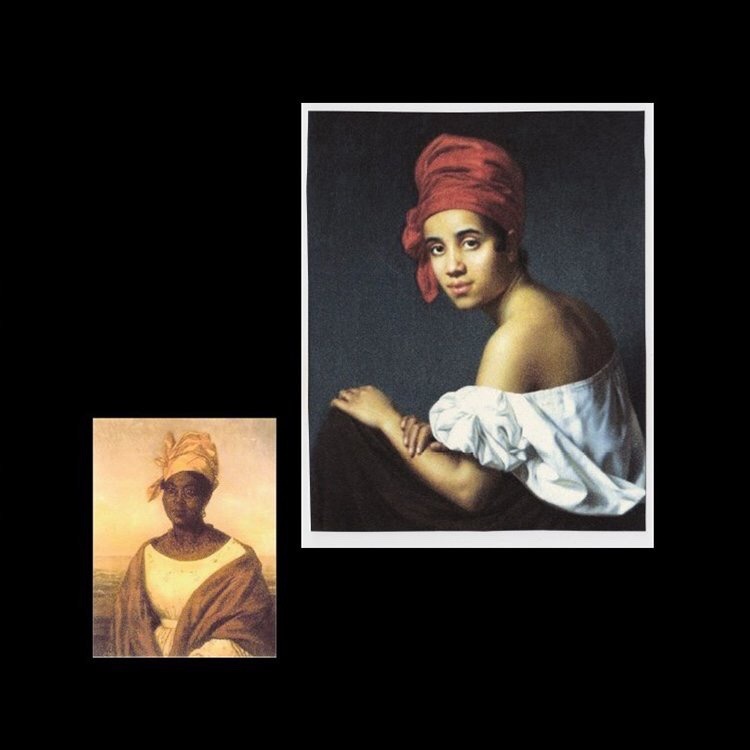

Unfathomable City: A New Orleans Atlas makes it a point very early on to highlight the unique ways in which the city and its residents are at once separated by distinct cultural and geographical markers and pushed together due to lack of land and the very human tendency to commune and exchange culture. In the 1700s, racial, religious, and economic segregation stemming from early immigration, slavery, and the ever-present class divides of an ever-evolving city created a society that simultaneously seems cavalier in its racial mixing and archaic in it its laws and resulting subjugation of the products of it. Gens de couleur libres (free people of color) occupied a space between privilege and extreme oppression that meant they adhered to a unique set of laws made, in some cases, to distinguish them from the enslaved Africans they had seemingly transcended and the white New Orleanians that still viewed them as being distinctly “other.” One of these such laws meant to prevent those of African descent, specifically women, from transcending blackness completely were the Tignon laws.

These laws, and the scarves themselves, though meant to subjugate, degrade, and continue the nation’s sordid history of policing black femininity and presentation, were reinterpreted by women of color in extraordinary ways that can still be seen in African-American culture today. Creole women of color who had previously decorated their hair with feathers and jewels did the same with lushly colored scarves that became more of a statement of beauty than a punishment. This form of aesthetic protest became not only a declaration of pride but a positive marker of a culture unique unto itself. In recent years, various interpretations of tignons have experienced a cultural resurgence as women of the African diaspora continue to look to the past and find strength in this unique historical example of ingenuity in the face of institutional debasement.